My Flag Design Principles

Formed from data, opinion, style, and identity shaped via 300+ portfolio designs

In 2024, I did a research paper using flag ratings data to parse out how influential various flag design features were to the ratings of a flag, and presented it at the North American Vexillological Association (NAVA) conference in St. Paul’s, Minnesota. This is a layman’s summary of that research so as not to bore anybody with the math and statistics, and how the research results influenced my design principles. While on design principles, I’ve also added some of my design principles beyond what the research was able to measure, and why I have all of them.

Research Methodology

The research combined ratings from three NAVA surveys (2001, 2004, 2022) of US state flags, Canadian provincial flags, and US city flags, where participants rated flags on an integer scale from 0 to 10. There were 534 flags rated by 3770 raters. Flags all had elements classified for features according to a system I created from features I had to classify in the flags rated, because I wasn’t able to find a system that covered all the features sufficiently and clearly. Average ratings of flags with and without each feature was compared to see if there was statistical significance (2 standard deviations), with significance meaning the principle can be suggested for contributing to well-rated flag design (or avoidance for contributing to poorly rated designs). This is important to re-emphasize because in some cases, there was a notable gap in average ratings that may seem to suggest a different to someone just looking at the results. However, it wasn’t big enough to be statistically significant by the math to be designated as a principle derivable from the research, so it wasn’t. Lack of designation doesn’t always mean the average ratings between groups were quite similar, and additional information from future surveys may change current conclusions, but the ratings gap and/or sample sizes would have to be even bigger to offset results derived from current data showing no significant difference.

Now, flags all come with multiple features, so one cannot theoretically test solely one feature against the lack of it, but the theory is that there would be enough flags with and without every feature tested, that the various other features present would either balance out and cancel each other, or be present often enough to be considered as an influential characteristic of the feature that it is fair to include that influence as part of the feature’s rating impact, like text in seals on flags. The sufficient flags sample size was not an assumption, though, and was tested with each feature for groups with and without the feature. Almost every feature tested had sufficient sample size to carry out the comparison otherwise with statistical reliability.

Principles Derived

The principles derived were results where there was statistical significance between average ratings of flags obeying and disobeying the principle tested. For the most part, they agreed with principles in Good Flag, Bad Flag (GFBF) by Ted Kaye. Perhaps more interesting was that principles derived provided clarity on features GFBF were silent on, like approved usage of four colours. Two or three colours were suggested, while five or more were discouraged, but nothing had been said about four colours. There were also other features not mentioned in GFBF that were tested, because as a designer, I knew they were influential in designs being appealing or unappealing, like symmetry and colour contrast.

The results derived also generally agreed with a different style of quantitative analysis that Ted and his son, Mason, did some years back before the 2022 survey, including magnitude of influence like text on flags being the most damaging to a flag’s design rating. I won’t go into that analysis’ methodology, but it’s good to know the two different approaches generally agreed to avoid controversy and confusion. My approach is less objective in feature assignment, though, being classified as present or not, rather than extent of presence, and can be replicated with future surveys (preferably with the same 0-10 rating scale), then split to see if opinions have changed over time, or if different demographics rated differently, and so on, as was shown with the 2022 NAVA survey results when they were presented.

In the general order of GFBF principles, and relating to them where no GFBF equivalent were present, here are the flag design principles derived, and a little word about each.

Simplicity

Design flags that can be drawn with 2-5 lines of instruction. Quantifies designs simple enough a child could draw it from memory. Some lines may refer to a group of charges or elements, like “3 identical red stars across the top” (Washington DC).

Use up to 4 unique charges. Charges are each a unique element, not groups of elements like sun, moon, and 4 stars, unless the multiple charges were identical, like 4 identical stars in a group.

Avoid “official charges”. Official means recognized designation through formal adoption, like a coat-of-arms, logo, seal, etc. These are often collection of charges with more than 4 unique. Official charges also often have lettering, which further brings down the rating of the flags they are on.

Avoid single colour fields and border fields. Single colour fields are the “bedsheet” designs, among which white fared the worst, though not quite with statistical significance. Border fields look like a framed bedsheet.

Use any symbol, so long as meaningful and simply rendered. No flag sets with any symbol types, like stars, transportation, water, etc. rated significantly higher than any other. That includes the ever popular star, figurative or celestial.

Colours

Use 2-4 colours. GFBF recommended 2 or 3 colours, and discouraged from 5 or more colours, but was silent on 4 colours.

Use any colour, basic or non-basic, and multiple versions of the same colour (counted as 1), including for the dominant colours. Production costs might be higher for flags with non-basic and multiple versions of one colour, pending method of production. However, the trade off is for distinctiveness, and maybe more meaning to have a more appropriate shade or tint of a colour like blood red versus generic fire engine red to represent blood.

Have high contrast among colours. Contrast can be qualitatively gauged by converting the full colour flag graphic into a grayscale one to see how well the design can still be perceived, or not.

Lettering

Avoid lettering, except for large, left and right mirror symmetric letters like A or M (in certain fonts). These seem to be acceptable as symbols, so long as they are properly readable from both sides of the flag.

Principles adherence

Adhere to 4 or 5 of the GFBF design principles (and supplementary principles here). There was a distinct average ratings difference between flags adhering to 4 or 5 of the principles, compared to those adhering to 3 or fewer. So adhering to a few won’t just cut it for a well rated design!

My Additional Flag Design Principles

Flag design principles that can be conveyed for following are useful, but they have to be definable in some way, quantitatively or qualitatively. In figuring out and fine tuning my design style, identity, and tendencies over 300+ proposed designs of a portfolio on my idesignflags Instagram, I have embraced several other principles that are more challenging to “instruct” for how to follow, and/or measure to prove their value. Fortunately, I don’t have to do that for my personal style, but I think they would be valuable for others to consider in designing flags, or judging flag designs beyond a quick rating, like finalists in a competition. In no particular order:

Design to capture the “soul” of the entity. Meaning to capture the nature of its people and culture. This is probably impossible to define to convey, but I ask myself if the adjectives (words or phrases) I would use to describe the place and its people could also be used to describe the flag design. Examples I tend to give with select designs from my portfolio include artsy, independent, strong, ambiguous, multi-faceted, quiet, peaceful, etc.

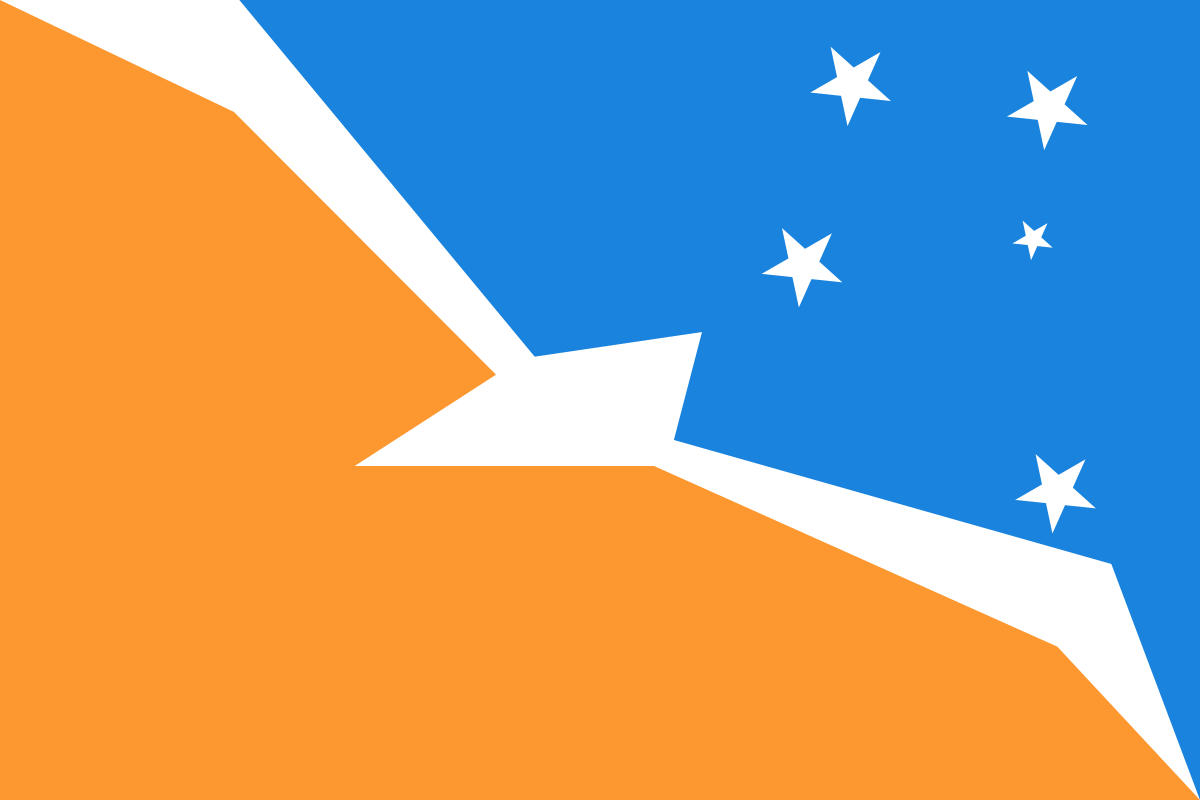

Create image designs when possible (meaningful symbols). These are basic renderings of an image. Iconographic vexillolography? I love art, and if the symbols could be combined to form an image rather than an arranged collection of objects like the heraldic approach often yields, I am going for it! It will make a much more distinctive and memorable design than that laid out collection of objects. Look at the image design on flag of Tierra del Fuego, and see if you think it’d be more distinctive or memorable with a seagull and stars of the Southern Cross laid out side by side, with the latter possibly looking like a dead bird on the ground silhouette. It also wouldn’t “feel” like Tierra del Fuego. Both, my personal flag and that favourite flag are image designs, and are such for a reason!

Use of non-traditional colours appropriately (meaningful, high or at least medium contrast). As a former graphic designer, I know that in branding, basic colours convey cheap and common, while rarer shades and tints, or uncommon colours like brown and teal, convey class and value. My colour preferences in anything also involves less common shades and tints, aside from black and white that have none (colour gray). I was happy that my research showed no preference for basic or non-basic colours used.

Use of uncommon colour combinations appropriately (meaningful, high contrast). Similar to basic colours in branding, overused colour combinations like basic red, white, and blue, also convey cheap (or at least not well thought out) and common. There are times and places for it, like American flag reference, but if not, at least use rarer shades and tints for what they might represent, like crimson for blood, white, and sky blue for open skies. However, I tend to lean towards colour combinations entirely uncommon for colours used, not shades or tints of them, like brown, white, and navy. I’m glad my research showed my designs using such uncommon combinations and non-basic colours are not at a disadvantage for design ratings. If you want help with uncommon colour combinations, look to US college sport team colours, among other places, but that’s my starting place.

Use 4 colour combinations appropriately (meaningful, high contrast), when possible. It gives an additional symbol over 3 colour designs, expands the possibilities of colour combinations, with emphasis on uncommon colour combinations because most people think of colour combinations in triads. If you look at the evolution of American professional sport uniforms, many teams now either have combinations of 4 colours, or “alternate” jerseys with 4 colours. I’m also glad my research showed 4 colour designs were just as well rated as 3 colour designs, and almost significantly better than 2 colour designs, so the suggestion or approach to use 4 colours in appropriate manners isn’t an “opinion” or “hot take”. Despite this willingness to use 4 colours in my designs, most of my portfolio designs have 2 or 3 colours.

Use as many colours as I can justify, appropriately (meaningful, high contrast). With digital printing of flags, colour printing on paper, and colour rending on screen being able to produce millions of colours, I see no reason why, so long as the colours are meaningful and rendered with high contrast, there can’t be such designs.

Use uncommon symbols appropriately (meaningful, simple rendering). How many things are there that can represent a place or entity or group of people? Use them then, rather than resort to stars, points on stars, or other more abstract symbols, especially for towns and cities that have very specific identities rather than states or nations that have to avoid having a symbol for everything or every group or place within, and possibly rightfully, use stars and other abstract symbols! Uncommon symbols will also the design more meaningful in being specific, and memorable for the uncommon symbol, or at least not be confused with many other designs bearing only common symbols.

Include obscure symbolism (aka “Easter eggs”), when possible (meaningful, simple). Most people get excited about flags with some trivia associated with their design, whether finding out or telling others about it like it’s a secret they know. Additional symbolism also makes a flag more meaningful, with the subtlety being able to capture aspects harder to render as a graphic, whether for the graphic itself, or due to clutter of items that would have to be in the design. An example could be the official PANTONE Baltic green colour I used for wavies to represent the Baltic Sea in my winning design for Flag Focus’ Baltics Bonanza competition to design a flag for the Baltics region around the Baltic Sea. That colour was determined to be the best representation of general colour of the Baltic Sea by some colour experts, so why not use it instead of some generic blue one might have used for water and wavies? It’s more meaningful, and distinctly more memorable, and it’s not like someone wouldn’t get it represented water in being used to colour the wavies. In fact, it would peak their curiosity to ask “what’s with the teal like green wavies instead of blue”? Hopefully, they’d enjoy the Easter egg trivia answer as well.

Design asymmetrically, when appropriate. I’m sure if I had enough symmetric flags rated in my research data, it would show that flags symmetric in some way in their design would rate significantly better than those without any symmetry. The ratings gap was that big. Just not enough sample size for statistical significance. Flags with horizontal mirror symmetry also can’t be flown upside down, which happens more often than one might think, it seems, so there is practical value to the symmetry. Their designs are also easier to remember because it’s just a portion of the flag replicated to the rest. Finally, we are programmed to love symmetry as part of our judgment of beauty like in faces, bodies, animals, flowers, and so on. However, I like asymmetry for its distinctiveness, and think it’s fine given I’m not designing anything natural like a face that might be argued to be symmetric by default. For designs, I use software so it is easy to do symmetry, possibly harder than asymmetry if you eye-balled things rather than use geometry like I do. However, for creations like garments that I do in fashion design, symmetry requires perfection, and I just admit I am human to do asymmetric designs, leaving perfection to “God”. I extend that to all designs I do, when it’s appropriate, to be a clear identity aspect of my general design approach and style, rather than just for some things like garments.

Design to peak curiosity, preferably in “good” ways. “Good” would be impossible to define, but ask yourself this. Would you rather have a flag that is only slightly likeable or neutral for reactions elicited, or would you rather have a flag that lots people want to know more about when they see it? Ideally, you’d have a design that is, both, very popular and peaks curiosity of people when they first see it to want to know what it represents, or know something more about it if they saw it with what it represented. But for me, if I can get a pass with a neutral reaction, I’ll take the more interesting design every time. Grabbing people’s attention and drawing people in are part of marketing, and a flag is marketing like a brand for the entity. The flag will also be more memorable if people want to know more about it and get their answers. They might even tell others about it without solicitation!

Give the design a nickname or moniker of 1 or 2 words, like “Old Glory”. Nicknames and monikers are very endearing to people. Beyond the design, you can make a design more likeable with a good nickname or moniker. It can also then be easily written about in poetry, songs, speeches, etc. that can further endear it to the people compared to “the flag of X”.